CPEC at Ten: Unpacking the Challenges

A Decade of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.

versão portuguesa disponível

Strategic Achievements, Political Risks, and the Geopolitical Shifts Reshaping South Asia

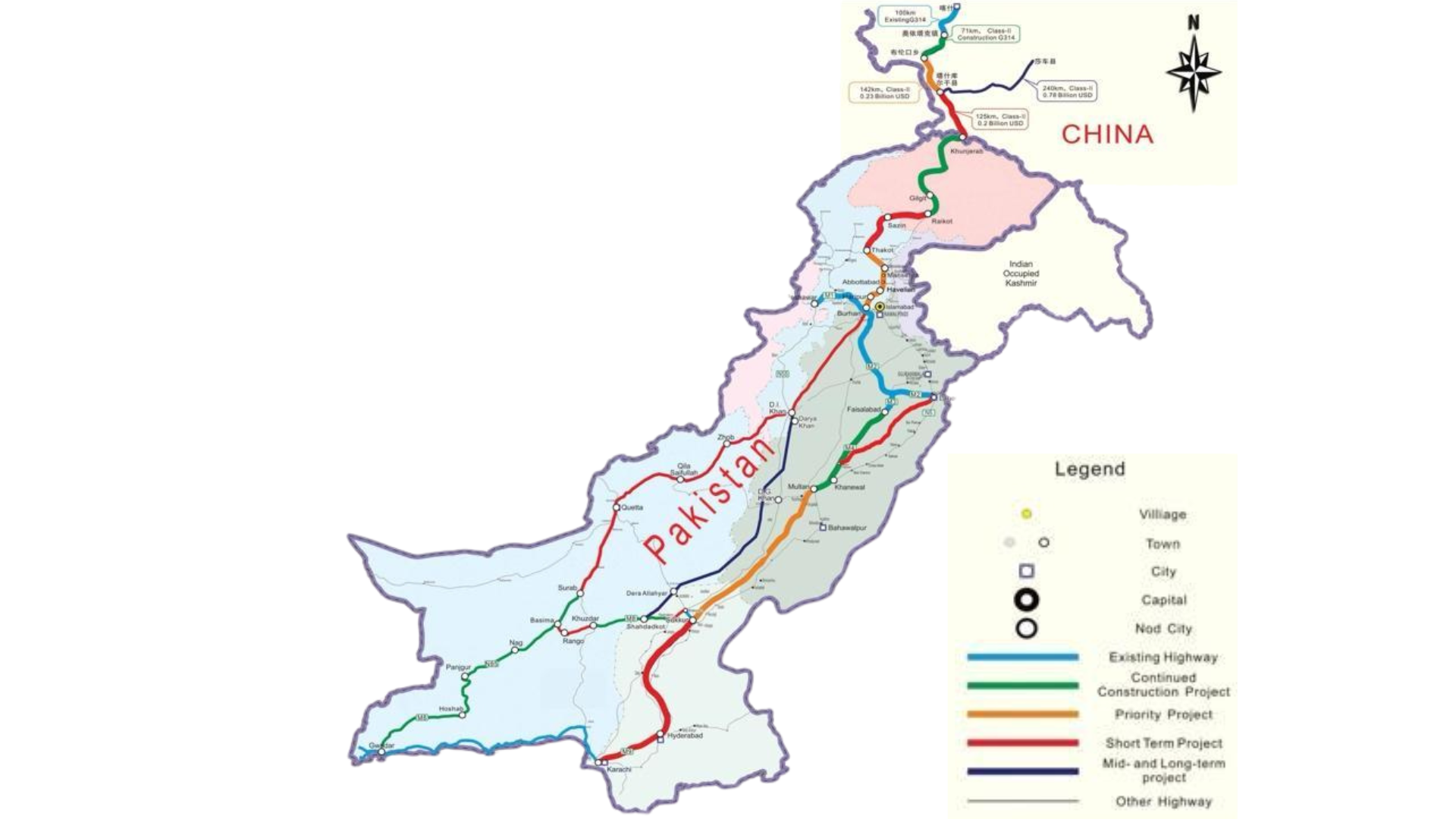

In July 2013, Pakistan's Prime Minister, Nawaz Sharif, signed an agreement to develop the Long-Term Plan for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC—figures 1 and 2).

The said Corridor was and continues to be centered on connecting the Chinese city of Kashgar to the Pakistani port city of Gwadar. It was formally launched during Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Pakistan in 2015. Initially, CPEC was described as a $46 billion investment, but it is now estimated at around $62 billion. Its outlay is equivalent to the total investments made by China in Pakistan between 1970 and 2015.

Divided into three phases, CPEC incorporates many projects to accelerate infrastructural, industrial, and socio-economic development.

CPEC, a cornerstone of China's regional policy, stands as the flagship project of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Now entering its second phase, CPEC was initially focused on improving infrastructure and connectivity. Its key parts included projects on energy installations to address Pakistan's energy crisis and those on the construction of highways, railroads, pipelines, and fiber optic networks linking China's western region to the Arabian Sea through Pakistan's deep seaport in Gwadar.

This provides direct access to the Indian Ocean and a shorter route for oil supplies from the Middle East and Africa. [1] Beijing not only looks at CPEC as a project of infrastructural development and connectivity but also as a gateway to regional integration for peace and prosperity and to build a “Community of a Shared Future.” This also reduces its dependence on the Strait of Malacca, a strategic chokepoint that the United States could easily block in times of conflict.

The project promises to bring economic benefits to Pakistan through investments, employment, and closer ties with the world's second-largest economy. [2] Examples include the investment in expanding Pakistan's electricity grid by adding 13,000 MWs, of which 10,000 MWs were completed by 2018. This investment in the energy sector is essential for CPEC and aims to reduce Pakistan's pre-2018 energy deficit. This energy increase would help revitalize the industry and add 2% to the country's GDP. [3]

Furthermore, road and rail infrastructure investments are expected to facilitate the transportation of goods and boost local tourism. Destined for Gwadar, these goods will consist of Chinese and Pakistani products intended to be exported to other continents.

Additionally, there are plans to construct 46 Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in Pakistan, with incentives for foreign investment and economic freedoms to develop industries. [4]

In order to develop the port of Gwadar, thirty organizations have already invested in the free trade zone, and millions have been allocated to its development. Initiatives include the development of the University of Gwadar, promoting the steel and petrochemical industries, and improving fishing and shipbuilding. Due to its strategic location near the Strait of Hormuz, which handles between 20% and 30% of international oil trade, this port city has the potential to become a regional trading and transit hub. [5]

Notably, 36 projects were completed in the first phase of CPEC in July 2021. These projects included infrastructure, energy, and socio-economic development, especially those in Gwadar. [6]

The completed initiatives are considered early-harvest projects aimed at improving transportation and connectivity and boosting the confidence of private investors. [7]

CPEC Phase

In 2024, CPEC entered its second phase, which experts and policymakers regard as a transformative initiative for Pakistan and the broader region. This phase is expected to drive Pakistan's technology transfer and industrial growth. Speaking at the 75th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China, Pakistan’s Prime Minister, Shehbaz Sharif, highlighted the [vast potential for cooperation]https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2019/12/strategic-implications-of-the-china-pakistan-economic-corridor-december-16-2019?lang=en) in agriculture, information technology, mining, and other key sectors.

In phase 2, Pakistan plans to complete 70 projects. China and Pakistan are committed to jointly launching five new corridors: the Growth Corridor, Economic Development Projects Corridor, Invention Corridor, Green Corridor, and Regional Connectivity Corridor.

Challenges and Impediments to CPEC

CPEC has been rightly viewed as a pivotal initiative for reviving Pakistan’s economy and turning Sino-Pak relations into a strategic and economic partnership. However, since the project's launch, many hiccups have slowed it down. One of the significant challenges to CPEC is the security of the projects.

Chinese nationals and Pakistani security forces have long been the targets of separatist militant groups like the outlawed Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) and Balochistan Liberation Front (BLF), which claim that China and Pakistan are usurping their land and resources.

Similarly, other terrorist outfits, such as Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and its splinter groups, have targeted Chinese nationals working on different projects in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). Since the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan, TTP has become more belligerent and has increased its terrorist activities in Pakistan.

In recent years, the security of Chinese nationals has become a major challenge for Pakistan. There have been several major attacks on Chinese nationals working on different projects, which have led to growing Chinese concerns. They have termed such attacks unacceptable and a primary challenge to CPEC.

Indeed, the deteriorating security situation has hurt CPEC, negatively impacting Chinese firms’ capacity to enhance their Pakistan activities. As a result, China is mulling over instituting joint security mechanisms with Pakistan. This marks a significant policy shift, highlighting the seriousness of the situation.

Political instability and polarization in Pakistan have also contributed to CPEC’s slowdown. Currently, Pakistan is grappling with one of the most serious political upheavals since its disintegration in 1971.

Unstable political processes, frequent changes in government policies, corruption, favoritism, political polarization, and administrative prioritization of different aspects of CPEC have hindered the project’s progress.

This set of grievances has led to resentment in some provinces, as evidenced by demands to increase the pie size for them. These issues have been exploited by separatist and sub-nationalist groups, such as the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM) and the Baloch Yakjehti Committee. [8]

All this contributes to making the situation all the more complex. China has taken cognizance of these issues, calling upon Pakistani authorities to end political instability.

Another major hurdle for CPEC is the set of geopolitical rivalries involving Pakistan, India, China, and the U.S. Foremost. CPEC’s route passes through Gilgit Baltistan (figure 3), a territory administered by Pakistan but claimed by India.

New Delhi considers this project a violation of its sovereignty. India also perceives BRI as a threat since it provides China with land connectivity to the Indian Ocean Region.

Moreover, the growing competition between China and the U.S. has also cast a shadow over CPEC. The U.S. perceives that CPEC enhances China’s influence in South Asia and the energy-rich Arabian Peninsula. It thinks CPEC, as part of BRI, will pose a major challenge in the Indo-Pacific and is a manifestation of China’s predatory economics.

New Delhi’s and Washington’s opposition to BRI and, by extension, CPEC should be seen as a bigger geopolitical problem, not least because both countries have deepened their strategic partnership to counter China’s growing forays in the region.

Indeed, CPEC will also help bolster China's economic security as its new land route is set to reduce its exclusive dependence on the Strait of Malacca. In addition to securing an important maritime trade route for importing oil from countries like Saudi Arabia and Iran, this conduit will allow China to increase its electronics and other manufactured goods exports to the Middle East and Africa.

Diversifying its trade routes will make its supply lines relatively less vulnerable to punitive actions. Therefore, in order to counter China, both India and the U.S. will find it helpful to impede CPEC and BRI.

Conclusion

All in all, CPEC, which is designed to give China greater access to West Asia and beyond, is beset with a plethora of challenges. A primary geopolitical concern emanates from the Indo-U.S. opposition to the project. This is primarily because China’s bid to increase its clout in the Indo-Pacific is seen as a threat to what the U.S. calls a rules-based order.

Given that India is China’s adversary and a U.S. partner, it will continue to be a major project opponent. This will vitiate its ties with China and Pakistan, posing a significant challenge to CPEC.

On the domestic front, security concerns and political instability in Pakistan will continue to affect CPEC’s progress negatively.

References

- Mari Izuyama and Masahiro Kurita, “Security in the Indian Ocean Region: Regional Responses to China’s Growing Influence,” The East Asian Strategic Review, 2017.

- Rabia Akhtar, ed., China-Pakistan Economic Corridor Beyond 2030: A Green Alliance for Sustainable Development." (Islamabad: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2024).

- Ammar Karim, “China Pakistan Economic Corridor:,” Coleção Meira Mattos: Revista Das Ciências Militares 16, no. especial (September 9, 2022): 87–103.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ammar Karim, “China Pakistan Economic Corridor.”

- Dr. Raja Amir Hanif, Ms Iqra Sultan, and Mr M. Haqeeq, “POLITICAL POLARIZATION ISSUES AND CHALLENGES FACED BY PAKISTAN,” NDU Journal 38, no. 1 (March 29, 2024): 35–44.

The opinions expressed in this article do not reflect the institutional position of Observa China 观中国 and are the sole responsibility of the author.

OBSERVA CHINA 观中国 BULLETIN

Subscribe to the bi-weekly newsletter to know everything about those who think and analyze today's China.

© 2025 Observa China 观中国. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy & Terms and Conditions of Use.